I can already feel the headwinds of protest this pensée is likely to engender, so to mitigate their ferocity, allow me to open with these caveats:

- I’m not against people taking electronic gadgetry to the slopes. On the contrary, I’ve created an app for ski testers to record their results, a gadget if there ever was one. I’m all for apps that help people extract more enjoyment from their ski day or serve some safety function.

- I’m not trying to rate or evaluate the existing apps that, among many other functions, try to measure the skier’s maximum and average speed. There are possibly some extant or in the offing that skirt the issue I’m about to illuminate.

- I realize the speed assessments of former world-class speed skiers provide only anecdotal evidence, but there’s only so many people who’ve gone over 125mph who can speak from personal experience on the subject of just how fast is fast.

- I like speed. One of the main reasons I ski is to experience a sensation close to flight. I ski on equipment appropriate to the task, always maintain control and try to be the best fellow citizen I can be on my way down. Point being, like almost everyone reading this, I like to go fast and occasionally I’m curious as to how fast I went.

- I make no pretense about being a scientist, but I do have a technical background and am fortunate to have several gifted scientists with whom I can consult. If one takes the long view, this subject intersects with many fields of inquiry, but it’s based on science and how it’s applied.

- This piece is ungodly long for an online essay, for which I apologize. Please don’t shoot the messenger. I already feel like a cat-lover forced to give his adored pet a pill, in my case a reality pill that may stick in a few throats.

I’ll always remember the first time I used Ski Tracks, the smartphone app that pioneered GPS-based skier tracking and is still the industry benchmark. It was February 11, 2014, the day before the Mammoth Trade Fair was scheduled to convene. The weather was ideal, the skis were perfect and plentiful and my wingman was the always reliable Theron Lee.

We were on about our third skis of the morning when it occurred to us to turn on the new app that we heard could record our speed and just about anything else measurable during a ski day. We didn’t change our routine one iota; we were testing skis after all, and consistency matters in this enterprise. We zipped our phones back in our pockets and didn’t pull them out again until two runs later.

As we looked at our recorded results for the first time, we both started to break into broad grins and slowly shake our heads.

“What speed you got?” Theron asked, showing me his screen.

“72.3mph,” I replied, almost choking on the first chortle.

“70.8,” said Mr. Lee in reply to the question I didn’t have to ask.

And we laughed.

For we knew, without further analysis, that it was incontrovertibly impossible for either of us to have even approached such a speed. We wiped the tears from our eyes so we wouldn’t fog our goggles and went on about our business.

Later that day, Theron and I were skiing in loose tandem, as ski buddies often do, when a two-track super-carver in a one-piece suit insinuated himself into our line of travel, eventually colliding with Theron and sending him ass-over-teakettle into the trees.

If Theron had actually been going 70mph, he would have been swiftly killed, along with Mr. One-Piece-on-Rails. That both survived provided further evidence that the speed measurement part of the app we used that morning was, shall we say, off, and while that was interesting, figuring out why and how a measurement app might be off was far outside the scope of my competence.

In the years between now and then, the use of Ski Tracks and other apps intended to track your ski day has exploded. It’s hard to ride a lift without someone who is consulting his or her smartphone. Skiers seeking my advice on ski purchases, whether I encounter them online or in-store, often reference how fast they believe they ski.

I don’t know if there’s presently an app that has the speed-measurement problem solved, but I do know a lot of recreational skiers believe they are routinely skiing at top speeds in excess of 60 and even 70 or 80mph.

Balderdash.

Your clothing alone makes it impossible, a subject to which we shall return, but first let’s hear from that most reviled of social outcasts, a scientist, in particular the world’s foremost authority on skier fatalities (among other topics), Dr. Jasper Shealy, emeritus Professor of Statistics at Rochester Institute of Technology.

Shealy and his co-authors, Carl Ettlinger and Robert Johnson, published How Fast Do Winter Sports Participants Travel on Alpine Slopes? in the Journal of ASTM International (July/August 2005, Vol. 2, No 7, Paper ID JAI12092). Here’s some of the eye-opening data culled from their study:

- The average maximum speed for all observations, which included skiers and snowboarders, men and women, and covered all abilities, was 26.7mph.

- The highest mean speed for any group was for helmeted skiers in good visibility conditions: 31.5mph. (All recorded speeds were maximums.)

- Helmet users travel on average 3mph faster than non-helmeted users, generating 25% more kinetic energy than a non-helmeted user.

- When visibility is good, people go on average 5.2mph faster.

- Skiers travel 3.5mph faster than snowboarders.

After citing this seemingly mild differential, Shealy reminds his readers “kinetic energy increases as the square of the velocity. This means that the average speeds seen, for the two groups, skiers and snowboarders of equal mass, the average skier has 31% more kinetic energy than does the average snowboarder.” Meaning, when cultures collide, skiers hit harder.

Later in the study, Shealy notes “that fully 96.6% of the observations in this study were in excess of the ASTM helmet impact test speed [14mph/22.6km/h],” adding, “The kinetic energy of a person traveling at 43.0km/h [the average speed of 26.7mph recorded in the study] is 3.6 times greater than at 22.6km/h [the helmet standard].” The significance of this to skiers, Shealy wryly suggests, is “If you hit a tree at 30mph, you’ll need more than a helmet.”

Shealy avers that other speed studies conducted since the one referenced here don’t show dramatically different results. In abstract presented to the International Society for Skiing Safety at its 2015 conference, another speed study, titled Typical Skiing and Snowboarding Speeds at U.S. Ski Resorts, Shealy and co-authors Dr. Irving Scher and Dr. Stepan Lenka found that, if anything, the average speed of the total population of snow sliders in America was a little lower than the findings of the earlier study.

Dr. Scher happens to be chairman of ASTM F27 on Snow Skiing and Snowboarding; the subcommittee chair for ASTM F27.60 for Research and Statistics, and a USA delegate on the International Standards Organization committee TC83/SC4 on Snowsports Equipment. Not exactly a slacker in the credentials department. Scher’s verdict on speed-measuring apps gets to the point: “It’s dangerous for maximum speed to be the metric of success.”

The research of Shealy, Scher et al. suggests that GPS-based speed measurement may not jibe with other methods, like the use of photoelectric cells to trigger timing devices in international speed skiing events. Speed skiers’ times are determined by their average speed during a 100m speed trap, not the peak speed recorded in the Shealy study or the max speed as recorded by phone apps.

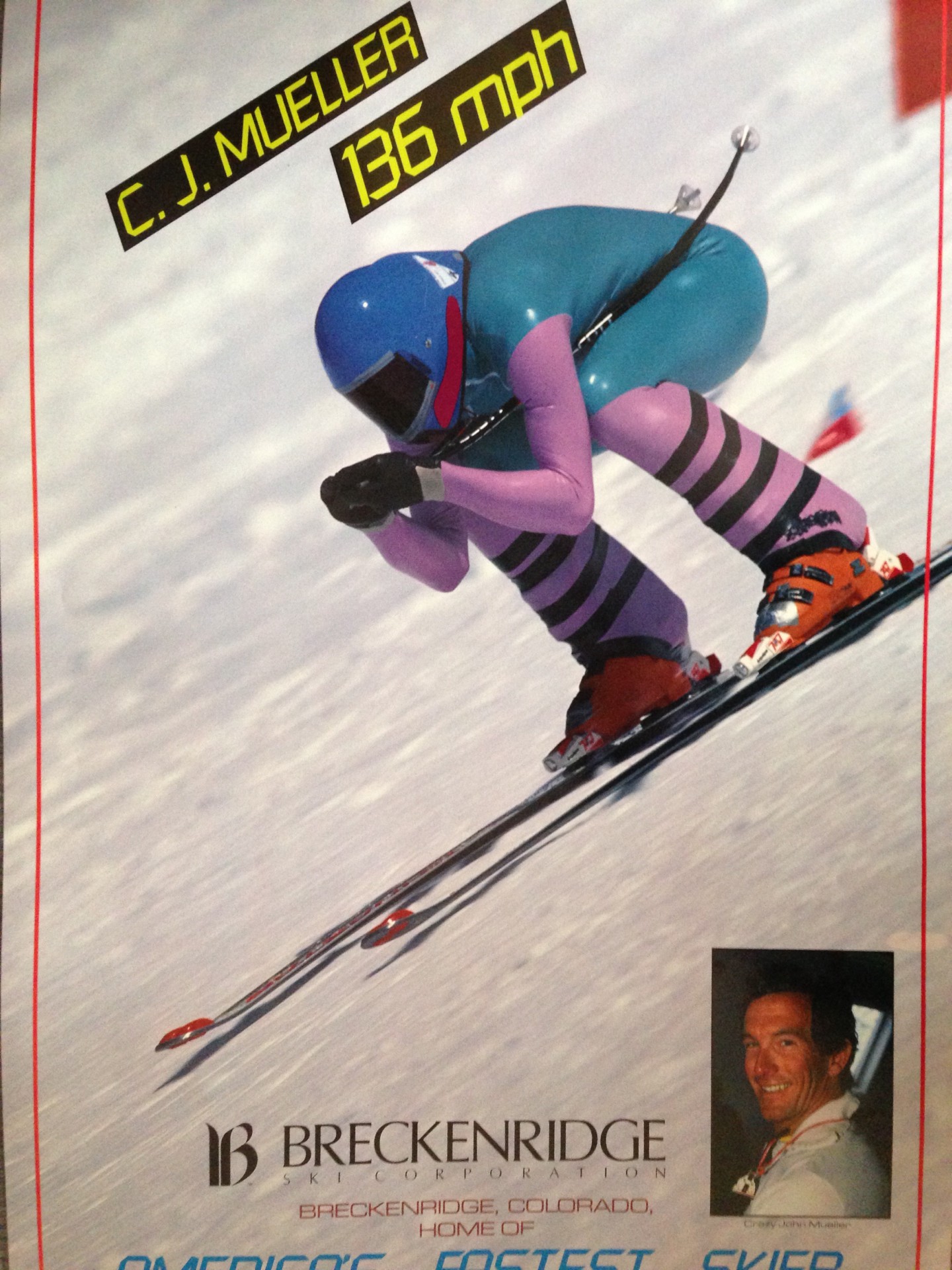

The testimony of speed skiers is relevant because this perforce small community knows what it’s like to go 60, 70, 80, 90, 100-plus miles an hour, and how different life becomes at each interval. I spoke with Jimbo Morgan and C.J. Mueller, who, along with medalist Jeff Hamilton, formed the US speed skiing contingent at the Albertville Olympics in 1992.

Morgan scanned his memory to find a reference that would link the recreational skier environment to high-speed skiing. He recalled how he and Hall-of-Famer Steve McKinney (who was then Morgan’s coach) went to Slide Mountain (now integrated into Mt. Rose) to train the year before the Olympics. They chose Slide because of its consistent pitch and absence of other skiers. They used their speed skis, but dispensed with usual suits, helmets and farings. “We could get up to around 80mph, but we knew how to maintain control at that speed and also knew how to get rid of it. The average skier carrying that much speed to the bottom would cartwheel past the lift, if they made it that far.”

Mueller, who was the first skier to break 130mph, estimates that 60mph is attainable without a speed suit as along as all other conditions are ideal, but that, in general, anyone in regular ski clothes has no chance to break 60mph. He recalls a rare in-resort speed event where he was timed at 83mph, “but I was in a full tuck, with a rubber suit, speed helmet and farings.” Not to mention speed skis, as opposed to fully rockered, 180cm all-mountain skis.

The easiest way to tell how fast you’re going is how much noise your clothes make. Both Shealy and the professional speed skiers reference 40mph as roughly when wind resistance starts to make a real racket. The rare skier who is rocketing along over 40mph can be heard coming ahead of his arrival. If you were able to go any faster, you’d tear your anorak off. As C.J. points out, “at 80mph, even regular downhill suits start to flap,” which is why speed skiers prefer less porous rubber onesies.

Dressed for success: if you want to ski as fast as C.J. (which stands, appropriately enough, for Crazy John), you have to dress like C.J., in helmet, suit and fairings.

So maybe some GPS-based apps are predisposed to overestimate skier speed. So what? If someone shaped like an avocado and as easy to fold, wearing a ski outfit blousy enough to accommodate a shoplifted turkey, thinks he goes 70mph, what’s the harm?

The harm is where inflated expectations often lead when male human beings are involved. If my phone says I’m going 60, I’ll see if I can go 65. I’ll show the guy who always whips my butt at golf that I can beat him by 20mph on skis. I’ll beat my phone, I’ll beat you, I’ll beat the mountain itself.

Now we have a problem, and I don’t think I’m imagining it. People who think they’re fast think they can go faster. “It’s false bravado,” observes the insightful Jimbo. “Ego gets involved, people define themselves by their speed. The app makes people brave, but your ego will write checks your body can’t cash.”

Morgan’s in favor of anything that gets more people psyched to go skiing. “[Speed-measuring apps] get people’s stoke on, encourage them to get out there, and that’s a good thing,” he says. “But skiing out of control and above your ability isn’t. Speed takes experience, the right equipment and specialized training to manage.”

Remember that kinetic-energy-velocity-squared business Prof. Shealy cited above? A 175-pound body hurtling through space at speeds it cannot control is a menace to itself and every living thing around it. If you hit a tree at 40mph, it will be scant consolation to your survivors that you thought you were going 80.

As I hope I’ve made clear, I haven’t the faintest idea how to apply one doozy of an algorithm to GPS data to correct for speed over-estimation. I can’t say with any certainty exactly how far off speed measurements may be in any set of circumstances. But I’m pretty sure people wouldn’t feel compelled to push to achieve a higher speed on crowded, public slopes if the most ego-gratifying claim they could make at the end of a blistering run is “I went 27.5!”

Before stepping off my soapbox, let me underscore a few salient points:

- No matter what you imagine, you aren’t going 70mph. Ain’t happening.

- People wouldn’t be as likely to ski beyond their abilities if their speeds were accurately recorded on apps that are now ubiquitous.

- There’s a place on the mountain where you can race without endangering yourself or your fellow man. It’s called NASTAR, a standardized racing format created by the brilliant John Fry, so that recreational skiers could use timed runs to improve their technique, engagement in and enjoyment of the sport.

Steve Wilson from Inside Tracks responds:

Dear Jackson,

My name is Steve Wilson I am the lead engineer on Ski Tracks.

Thank you for your interest in Ski Tracks and specifically the accuracy of the speed.

For the vast majority of skiers and boarders the speed errors are +/- 5% depending on conditions. Sometimes we do see inaccuracy in speed, this can be caused by a range of issues including interference, visible sky, weather or battery modes.

While we do see spikes in the speed – these are easy to spot and most users would know this is an error.

This season we are looking to reduce speed errors to +/- 1% making Ski Tracks probably the most accurate mountain tracking software.

We want all skiers to ski within control and follow the mountain code, in fact it is in the terms and conditions of Ski Tracks. Some users occasionally mention their top speed but the vast majority are more interesting in their verticals and distance. One million vertical feet is certainly more impressive than any speed.

I’m not sure I agree with the idea that any over speeds reported by Ski Tracks makes skiers go faster, if a user is trying to reach 70mph and Ski Tracks reports this incorrectly then the user has actually been travelling slower not faster.

With regard to the 47.6 mph shown on our screenshots – this is the maximum speed for an entire day and was actually obtained on an intermediate trail over a very short part of the day. The actual track was recorded by myself and was a test track that was compared with another GPS device.

From a technology point of view we try not to encourage dangerous skiing, in particular we do not show live speed (this is a huge distraction) on wearables or connected devices, nor do we provide leaderboards or segments.

We are more than happy to analyse any of your tracks regarding the speed. We can provide detailed analysis of the data.

If you have any further questions please do not hesitate to contact me.

Kind Regards

Steven Wilson